hikes <- read.csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/high_peaks.csv")3 Data viz

3.1 Background

We’re starting our unit on data visualization or data viz, thus skipping some steps in the data science workflow.

Mainly, it’s tough to understand how our data should be prepared before we have a sense of what we want to do with this data!

Warm-up (together)

- Convince ourselves about the importance of data viz.

- Explore the “grammar of graphics”.

Exercises (in groups)

- Explore how to create data viz in RStudio.

- Understand the different basic univariate visualizations for categorical and quantitative variables.

Watch:

- Intro to ggplot (Lisa Lendway)

- Univariate viz (interpreting) (Alicia Johnson) – you can ignore the parts about numerical summaries.

Read:

- A grammar for data graphics (Baumer, Kaplan, & Horton)

- Data visualization (Wickham, Çetinkaya-Rundel, & Grolemund)

- Visualizing distributions (Wilke)

- ggplot cheat sheet

3.2 Warm-up

The importance of visualizations

EXAMPLE 1

We’ll look at data on hiking trails in the 46 “high peaks” in the Adirondack mountains of northern New York state. This includes data on the hike’s highest elevation (feet), vertical ascent (feet), length (miles), time in hours that it takes to complete, and difficulty rating.

Insert a code chunk in one of 2 ways:

- Click the green code chunk button and select “R”.

- Use a keyboard shortcut!

- Ctrl + Alt + I (Windows and Linux)

- Command + Option + I (Mac)

Cut and paste the

hikes <- read.csv(...)code into your code chunk.Add a comment above the

read.csv()line describing what the code is doing.Run the code in the chunk in one of two ways:

- Click the green play button in the top right of the chunk.

- Use a keyboard shortcut!

- Ctrl + Shift + Enter (Windows and Linux)

- Command + Shift + Enter (Mac)

Open this data in a viewer in one of 3 ways:

- Click

hikesin the Environment tab. - Enter

View(hikes)in the console. - (NEW!) Ctrl+click (Windows) or Command+click (Mac)

- Click

As you look through the data in the viewer, try and answer the questions below. How easy is this? Type your reaction using one bold word and one italicized word.

- What patterns and trends are there in hiking trail

elevation? - What is the relationship between a hike’s

elevationand the typicaltimeit takes to summit / reach the top?

EXAMPLE 2

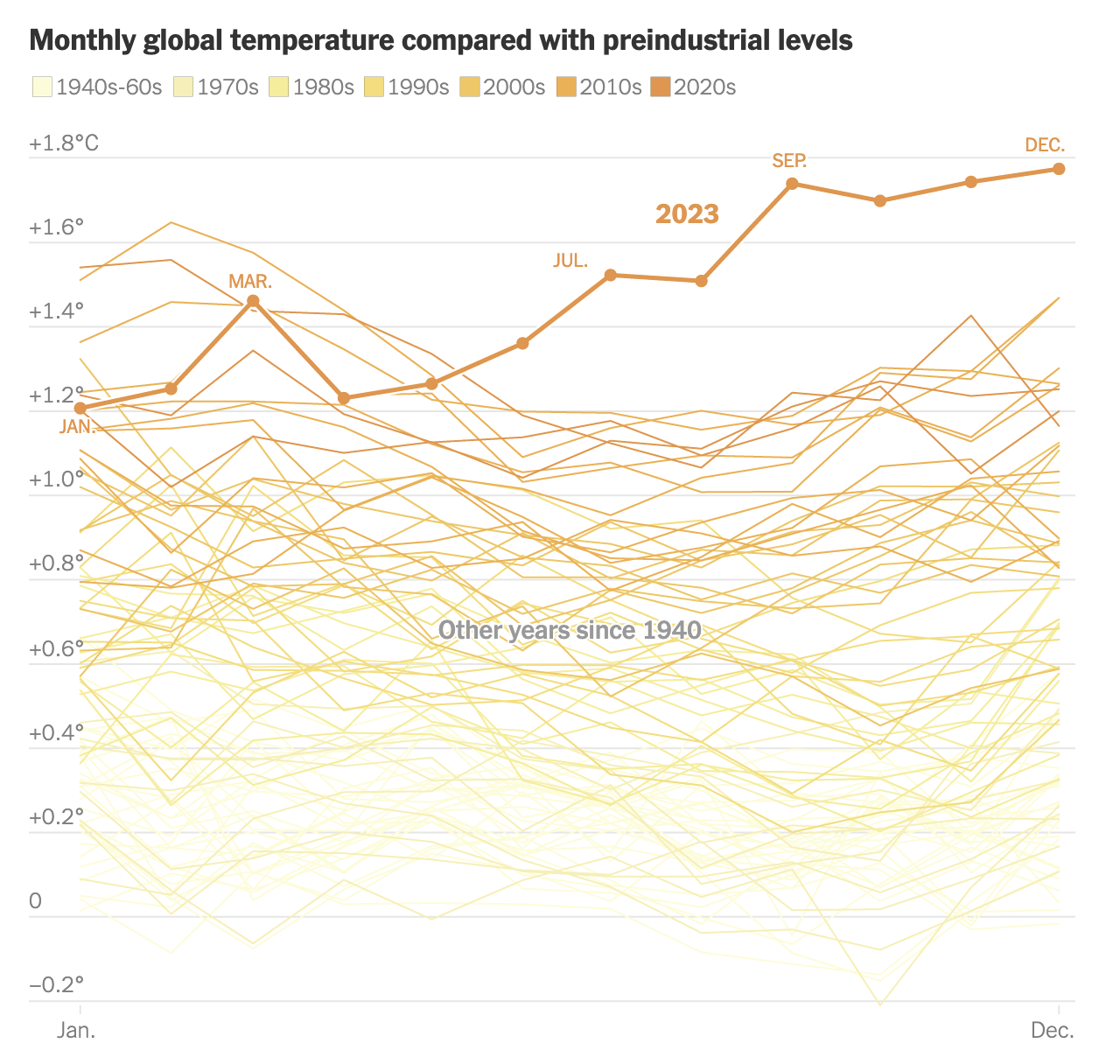

What if this New York Times article tried telling this story without using data viz? What would that story be like?

Group exercise: Collaborate with your group to brainstorm a paragraph that could try to take the place of this data visualization. (Feel free to talk it out or type it.)

Benefits of visualization

- Gain and communicate understanding with just a glance:

- scales & typical outcomes

- outliers (unusual cases)

- patterns & relationships

- Refine research questions & inform next steps of our analysis.

- Communicate our findings and tell a story.

Components of data graphics

EXAMPLE 3

Data viz is the process of mapping data to different plot components. For example, in the NYT example above, the research team mapped data like the following (but with many more rows!) to the plot:

| observation | decade | year | date | relative temp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2020-30 | 2023 | 1/23 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 1940-60 | 1945 | 3/45 | -0.05 |

Group exercise: Write down step-by-step directions to use a data table like this one to create the temperature visualization. A computer is your audience. Thus be as precise as possible, but trust that the computer can find the exact numbers if you tell it where.

COMPONENTS OF GRAPHICS

In data viz, we essentially start with a blank canvas and then map data onto it. There are multiple possible mapping components. Some basics from Wickham (which goes into more depth):

a frame, or coordinate system

The variables or features that define the axes and gridlines of the canvas.

NYT example: x-axis = date, y-axis = tempa layer

The geometric elements (e.g. lines, points) we add to the canvas to represent either the data points themselves or patterns among the data points. Each type of geometric element is a separate layer. These geometric elements are sometimes called “geoms” or “glyphs” (like heiroglyph!)

NYT example: add one line per year, add dots for each month in 2023scales

The aesthetics we might add to geometric elements (e.g. color, size, shape) to incorporate additional information about data scales or groups.

NYT example: color each line by decadefaceting

The splitting up of the data into multiple subplots, or facets, to examine different groups within the data.

NYT example: nonea theme

Additional controls on the “finer points” of the plot aesthetics, (e.g. font type, background, color scheme).

NYT example: NYT style

ggplot + R packages

We will use the powerful ggplot tools in RStudio to build (most of) our viz. The gg here is short for the “grammar of graphics”. These tools are developed in a way that:

- recognizes that code is communication (it has a grammar!)

- connects code to the components / philosophy of data viz

EXAMPLE: ggplot in the news

To use these tools, we must first get them into R/RStudio! Recall that R is open source. Anybody can build R tools and share them through special R packages. The tidyverse package compiles a set of individual packages, including ggplot2, that share a common grammar and structure. Though the learning curve can be steep, this grammar is intuitive and generalizable once mastered. Image source: Posit BBC on X

Follow the directions below to install this package, the directions depending upon whether or not you’re working on Mac’s server. Unless the authors of a package add updates, you only need to do this once all semester. To install:

- If you’re working on Mac’s RStudio server

tidyverseis already installed on the server! Check this 2 ways.- Type

library(tidyverse)in your console. If you don’t get an error, it’s installed! - Check that it appears in the list under the “Packages” tab (bottom right pane).

- Type

- If you’re working with a desktop version of R/RStudio

In the “Packages” tab (bottom right pane), click “Install”. From there type the name of the package (tidyverse), make sure the “Install dependencies” box is checked, and click “Install”.- Note: Another way to install packages is to use the

install.packages()function in the Console. Here you would enter:install.packages("tidyverse")

- Note: Another way to install packages is to use the

3.3 Exercises

Goals

We’ll talk more later about “good” data viz, and steps to think about when building viz. In these exercises, the goal is to:

- Familiarize yourself with the

ggplot()structure and grammar. - Build univariate viz, i.e. viz for 1 variable at a time.

- Start recognizing the different approaches for visualizing categorical vs quantitative variables.

Directions

- General

- Be kind to yourself.

- Collaborate with and be kind to others. You are expected to work together as a group.

- Ask questions. Remember that we won’t discuss these exercises as a class.

- Activity specific

- The best way to learn

ggplotis to just play around. Focus on the patterns and potential of the code. Don’t worry about memorizing anything yet! You will naturally start to remember the most important / common code the more and more you use it.

- The best way to learn

Exercise 1: Research questions

Let’s explore data from a transportation survey conducted by Macalester’s Sustainability Office in 2023. The aim of the survey was to understand patterns in transportation choices to and from campus.

A codebook (data description) is available here–have this open for reference throughout the exercises.

We’ll focus on exploring respondents’ primary mode of transportation (primary_mode_choice) and 1-way distance to campus (dist_1way_miles).

transport <- read.csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/mac_transport_survey_2023_clean.csv")

head(transport) response_date role on_campus_housing primary_mode_choice

1 2023-04-18T12:46:36Z Student Yes <NA>

2 2023-04-18T12:49:13Z Student No car/vanpool

3 2023-04-18T12:46:16Z Student No walk/cycle

4 2023-04-18T12:48:29Z Student No walk/cycle

5 2023-04-18T12:47:03Z Student Yes <NA>

6 2023-04-18T12:46:28Z Student No walk/cycle

primary_mode_text

1 <NA>

2 <NA>

3 <NA>

4 <NA>

5 <NA>

6 <NA>

perc_primary_mode

1 <NA>

2 80%

3 Probably about a 50/50 split between walking and taking the bus

4 95 percent

5 <NA>

6 100%

other_modes_choice

1 <NA>

2 walk, cycle or other non-motorized transportation,bus or other public transit

3 bus or other public transit

4 carpool or vanpool,Not Applicable

5 <NA>

6 Not Applicable

other_modes_text perc_other_modes dist_1way_miles gave_suggestion_comment

1 <NA> <NA> NA TRUE

2 <NA> 20% 1.0 FALSE

3 <NA> <NA> 0.6 TRUE

4 <NA> <NA> 0.5 FALSE

5 <NA> <NA> NA TRUE

6 <NA> 50% 0.2 FALSE- What features would we like a visualization of the categorical difficulty

primary_mode_choicevariable to capture? - What about a visualization of the quantitative

dist_1way_milesvariable?

Exercise 2: Load tidyverse

We’ll address the above questions using ggplot tools. Try running the following chunk and simply take note of the error message – this is one you’ll get a lot!

# Use the ggplot function

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice))In order to use ggplot tools, we have to first load the tidyverse package in which they live. Mainly, we’ve installed the package but need to tell R when we want to use it. Run the chunk below to load the library. You’ll need to do this within any .qmd file that uses ggplot().

# Load the package

library(tidyverse)

Exercise 3: Bar chart of transportation modes (part 1)

Consider some specific research questions about primary_mode_choice:

How many responses fall into each category? Are the responses evenly distributed among these categories, or are some more common than others?

All of these questions can be answered with a bar chart of the categorical data in the primary_mode_choice column. First, set up the plotting frame:

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice))Think about:

- What did this do? What do you observe?

- What, in general, is the first argument of the

ggplot()function? - What is the purpose of writing

x = primary_mode_choice? - What do you think

aesstands for? (Might not be obvious–see solutions if you’re unsure!)

Exercise 4: Bar chart of transportation modes (part 2)

Now let’s add a geometric layer to the frame / canvas, and start customizing the plot’s theme. To this end, try each chunk below, one by one. In each chunk, make a comment about how both the code and the corresponding plot both changed.

NOTE:

- Pay attention to the general code properties and structure, not memorization.

- Not all of these are “good” plots. We’re just exploring

ggplot.

# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar()# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar() +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses")# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar(fill = "blue") +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses")# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar(color = "orange", fill = "blue") +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses")# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar(color = "orange", fill = "blue") +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses") +

theme_minimal()

Exercise 5: Bar chart follow-up

Part a

Reflect on the ggplot() code.

What’s the purpose of the

+? When do we use it?We added the bars using

geom_bar()? Why “geom”?What does

labs()stand for?What’s the difference between

colorandfill?

Part b

In general, bar charts allow us to examine the following properties of a categorical variable:

- observed categories: What categories did we observe?

- variability between categories: Are observations evenly spread out among the categories, or are some categories more common than others?

We must then translate this information into the context of our analysis, here transportation choices at Mac. Summarize here what you learned from the bar chart, in context.

Part c

Is there anything you don’t like about this barplot? For example: check out the x-axis again.

Exercise 6: Sad bar chart

Let’s now consider some research questions related to the quantitative dist_1way_miles variable:

Among the responses, what’s the range of distances to campus and how are the responses distributed within this range (e.g. evenly, in clumps, “normally”)? What’s a typical distance to campus? Are there any outliers, i.e. responses that have unusually high or low?

Here:

- Construct a bar chart of the quantitative

dist_1way_milesvariable. - Explain why this is not an effective visualization for this and other quantitative variables. (What questions does / doesn’t it help answer?)

Exercise 7: Histograms

Quantitative variables require different viz than categorical variables. Especially when the quantitative variable has many possible outcomes, it’s typically ineffective to simply count up the number of times we’ve observed a particular outcome (as the bar graph did above). It gives us a sense of ranges and typical outcomes, but not a good sense of how the observations are distributed across this range. We’ll explore two methods for graphing quantitative variables: histograms and density plots.

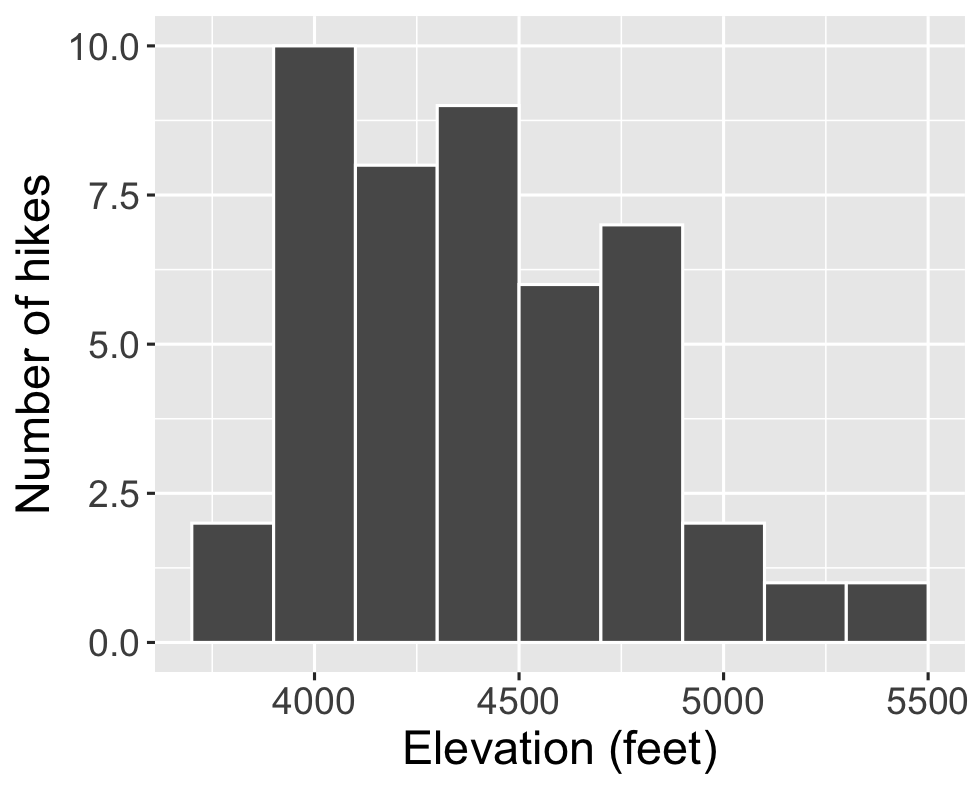

Histograms are constructed by (1) dividing up the observed range of the variable into ‘bins’ of equal width; and (2) counting up the number of cases that fall into each bin. Check out the example below from a different dataset on hikes in the Adirondack Mountains:

Part a

Let’s dig into some details.

How many hikes have an elevation between 4500 and 4700 feet?

How many total hikes have an elevation of at least 5100 feet?

Part b

Now the bigger picture. In general, histograms allow us to examine the following properties of a quantitative variable:

- typical outcome: Where’s the center of the data points? What’s typical?

- variability & range: How spread out are the outcomes? What are the max and min outcomes?

- shape: How are values distributed along the observed range? Is the distribution symmetric, right-skewed, left-skewed, bi-modal, or uniform (flat)?

- outliers: Are there any outliers, i.e. outcomes that are unusually large/small?

We must then translate this information into the context of our analysis, here hikes in the Adirondack Mountains. Addressing each of the features in the above list, summarize here what you learned from the histogram, in context.

Exercise 8: Building histograms (part 1)

2-MINUTE CHALLENGE: Thinking of the bar chart code, try to intuit what line you can tack on to the below frame of elevation to add a histogram layer. Don’t forget a +. If it doesn’t come to you within 2 minutes, no problem – all will be revealed in the next exercise.

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles))

Exercise 9: Building histograms (part 2)

Let’s build some histograms. Try each chunk below, one by one. In each chunk, make a comment about how both the code and the corresponding plot both changed.

# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram()# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white") # COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", fill = "blue") # COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white") +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 40) +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 0.5) +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")# COMMENT on the change in the code and the corresponding change in the plot

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 5) +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")

Exercise 10: Histogram follow-up

What function added the histogram layer / geometry?

What’s the difference between

colorandfill?Why does adding

color = "white"improve the visualization?What did

binwidthdo?Why does the histogram become ineffective if the

binwidthis too big (e.g. 40 miles)?Why does the histogram become ineffective if the

binwidthis too small (e.g. 0.5 miles)?

Exercise 11: Density plots

Density plots are essentially smooth versions of the histogram. Instead of sorting observations into discrete bins, the “density” of observations is calculated across the entire range of outcomes. The greater the number of observations, the greater the density! The density is then scaled so that the area under the density curve always equals 1 and the area under any fraction of the curve represents the fraction of cases that lie in that range.

Check out a density plot of 1-way distance to campus Note that the y-axis (density) has no contextual interpretation – it’s a relative measure. The higher the density, the more common are distances in that range.

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_density()Questions

INTUITION CHECK: Before tweaking the code and thinking back to

geom_bar()andgeom_histogram(), how do you anticipate the following code will change the plot?geom_density(color = "blue")geom_density(fill = "orange")

TRY IT! Test out those lines in the chunk below. Was your intuition correct?

- Examine the density plot. How does it compare to the histogram? What does it tell you about the typical commute distances, variability / range in distances, and shape of the distribution of distances within this range?

Exercise 12: Density plots vs histograms

The histogram and density plot both allow us to visualize the behavior of a quantitative variable: typical outcome, variability / range, shape, and outliers. What are the pros/cons of each? What do you like/not like about each?

Exercise 13: Code = communication

We obviously won’t be done until we talk about communication. All code above has a similar general structure (where the details can change):

ggplot(___, aes(x = ___)) +

geom___(color = "___", fill = "___") +

labs(x = "___", y = "___")- Though not necessary to the code working, it’s common, good practice to indent or tab the lines of code after the first line (counterexample below). Why?

# YUCK

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 5) +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")- Though not necessary to the code working, it’s common, good practice to put a line break after each

+(counterexample below). Why?

# YUCK

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) + geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 5) + labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")

Exercise 14: Practice

Part a

Practice your viz skills to learn about some of the variables in one of the following datasets from the previous class:

# Data on students in this class

survey <- read.csv("https://mac-stat.github.io/data/112_spring_2026_survey.csv")

# World Cup data

world_cup <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rfordatascience/tidytuesday/master/data/2022/2022-11-29/worldcups.csv")Part b

Check out the RStudio Data Visualization cheat sheet to learn more features of ggplot.

3.4 Wrap-Up

Today’s activity:

- Render when you’re done.

- If you’re working on Mac’s server, remember to download and store both the .qmd and .html on your computer.

- If you didn’t finish in class, no problem. Finish up outside of class and check solutions in the online manual.

- Let ideas percolate about today’s dataset in relation to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

- Does anything pique your interest?

- Does the Campus Center Info Desk still provide universal bus passes to students? (See here.)

Homework plan:

- Homework 1 is due today!

- The data viz unit will have 2 homeworks.

- Homework 2 will largely be drill / practice with some guiding prompts.

- Homework 3 will be provide more experience working in open-ended settings.

- Homework 2 is due Tuesday 2/10, but you should chip away at it slowly so that you have time to absorb and ask questions. It’s not designed to finish in 1 sitting.

- Now that you have experience with the flow of our class, think about how you want to stay engaged with the course, me, and your peers.

- Put these ideas into your Engagement Promise due Tuesday 2/3.

RStudio Housekeeping

We’ll type a lot of stuff in RStudio, much of it being mistakes. This gets thrown into a file called .RData.

When that file gets big, it can take up a lot of storage space, slow down your computer, and mess up your future code.

Do the following:

Ignore this file when opening RStudio, and delete it when closing RStudio. In the very top toolbar:

Tools > Global Options > General- UNclick the box next to “Restore .RData into workspace at startup”.

- Select “Never” in dropdown menu next to “Save workspace to .RData on exit”.

- Click OK

Restart RStudio occasionally, e.g. after every class period or two.

Change the default file download location for your internet browser

- Why? Generally by default, internet browsers automatically save all files to the

Downloadsfolder on your computer. This does not encourage good file organization practices. You need to change this option so that your browser asks you where to save each file before downloading it. - How? This page has information on how to do this for the most common browsers.

3.5 Solutions

Click for Solutions

Exercise 1: Research questions

- For example: how common is each mode of transportation? are any categories more common than others?

- For example: What’s a typical distance to campus? What’s the range in this distance?

Exercise 3: Bar chart of transportation modes (part 1)

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice))

- just a blank canvas

- name of the dataset

- indicate which variable to plot on x-axis

aesis short foraesthetics

Exercise 4: Bar chart of transportation modes (part 2)

# Add a bar plot LAYER

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar()

# Add meaningful axis labels

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar() +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses")

# FILL the bars with blue

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar(fill = "blue") +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses")

# COLOR the outline of the bars in orange

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar(color = "orange", fill = "blue") +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses")

# Change the theme to a white background

ggplot(transport, aes(x = primary_mode_choice)) +

geom_bar(color = "orange", fill = "blue") +

labs(x = "Transportation mode", y = "Number of responses") +

theme_minimal()

Exercise 5: Bar chart follow-up

Part a

- To indicate we’re still adding layers to / modifying our plot.

- Bars are the

geometric elements we’re adding in this layer. - labels

fillfills in the bars.coloroutlines the bars.

Part b

Most common is the use of single-occupancy gas-powered vehicles, followed by walking, biking, or other non-motor means.

Part c

I don’t like that the categories are alphabetical, not grouped by similarity in forms of transportation.

Exercise 6: Sad bar chart

There are too many different values of the distance variable.

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_bar()Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_count()`).

Exercise 7: Histograms

Part a

- 6

- 1 + 1 = 2

Part b

Elevations range from roughly 3700 to 5500 feet. Elevations vary from hike to hike relatively normally (with a bell shape) around a typical elevation of roughly 4500 feet.

Exercise 9: Building histograms (part 2)

# Add a histogram layer

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram()`stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value `binwidth`.Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_bin()`).

# Outline the bars in white

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white")`stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value `binwidth`.Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_bin()`).

# Fill the bars in blue

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", fill = "blue") `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value `binwidth`.Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_bin()`).

# Add axis labels

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white") +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")`stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value `binwidth`.Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_bin()`).

# Change the width of the bins to 40 miles

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 40) +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_bin()`).

# Change the width of the bins to 0.5 miles

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 0.5) +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_bin()`).

# Change the width of the bins to 5 miles

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", binwidth = 5) +

labs(x = "1-way distance to Mac (miles)", y = "Number of responses")Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_bin()`).

Exercise 10: Histogram follow-up

geom_histogram()coloroutlined the bars andfillfilled them- easier to distinguish between the bars

- changed the bin width

- we lump too many responses together and lose track of the nuances

- we don’t lump enough responses together and lose track of the bigger picture trends

Exercise 11: Density plots

The density plot tells us essentially the same information as the histogram, but we no longer have count information on the y-axis. (Densities have the advantage of being nicer to overlay than histograms–we’ll see this later!)

ggplot(transport, aes(x = dist_1way_miles)) +

geom_density(color = "blue", fill = "orange")Warning: Removed 51 rows containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_density()`).

Exercise 13: Code = communication

- Clarifies that the subsequent lines are a continuation of the first. That is, we’re not done with the plot yet. These lines are all part of the same idea.

- This is like a run-on sentence. It’s tough to track the distinct steps that go into building the plot.